In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Habit and Habitat of Wuchereria Bancrofti 2. Morphology of Wuchereria Bancrofti 3. Life Cycle 4. Pathogenicity 5. Prevention and Control of Disease Caused.

Habit and Habitat of Wuchereria Bancrofti:

Wuchereria bancrofti is a filaroid nematode, causing a very tragic, horrifying and debilitating disease known as filariasis. This disease has been known from antiquity and was the first discovery of insect (culex mosquito) transmission of a human disease.

In general, infection with any of the filarial nematode may be called as filariasis but traditionally, the term filariasis refers to lymphatic filariasis caused by Wuchereria or Brugia species. Filaroids are tissue dwelling parasites in all classes of vertebrates except fish.

The genus Wuchereria was named after Wucherer, a Brazilian physician who reported the presence of larvae in chylous urine in 1866. The adult female was described by Bancroft in 1876. Wuchereria bancrofti is distributed widely in tropics and subtropics of Asia (India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, China), Africa and South America.

Morphology of Wuchereria Bancrofti:

A. Adult:

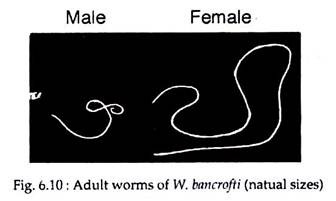

The adult worms are whitish, translucent, threadlike worms with smooth cuticle and tapering ends. The head is slightly swollen and bears two circles of well-defined papillae (Fig. 6.10). The mouth is small and lack buccal capsule. The female worm is larger (80-100 mm long and 0.24-0.3 mm wide) than the male (40 mm long and 0.1 mm wide) (Fig. 6.10).

The vulva is near the level of the middle of the oesophagus. Males and females remain coiled together usually in the abdominal and inguinal lymphatics and in the testicular tissue of human. The adult worms live for many years, probably 10-15 years or more.

B. Juvenile:

Female Wuchereria are ovoviviparous. The juveniles or embryos are released encased in its elongated egg shell, which persists as a sheath. These embryos are referred to as microfilariae. The sheath is delicate and close fitting but can be detected where it projects at the anterior and posterior ends of the microfilaria.

The embryos have colourless, translucent body with a blunt head and pointed tail, measuring about 250-300 µm in length 6-10 µm in thickness. It is actively motile and can move forward and backward, within the sheath.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

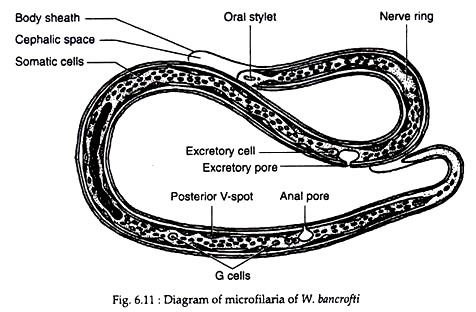

When stained with leishman or other Romanowsky stains, structural details can be made out. Along the central axis of microfilaria, a column of granules can be seen, which are called somatic cells or nuclei. At the head end is a clear space devoid of granules, called the cephalic space. In microfilaria bancrofti, this space is as long as it is broad.

In the anterior half of the microfilaria is an oblique area devoid of granules, called the nerve ring. Approximately midway along the length of body is the anterior V-spot which represents the rudimentary excretory system. The posterior V-spot (tail spot) represents the cloaca or anal pore. The genital cells (G-cells) are situated anterior to the anal pore, hi M. bancrofti, the tail tip is devoid of nuclei (Fig. 6.11).

The microfilariae circulate in the blood stream. In most Asian country including India, they show a nocturnal periodicity in peripheral circulation of human. It is seen in large numbers in peripheral blood only at night, between 10 pm and 4 am. This correlates with the night biting habit of the vector (culex mosquitoes).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Periodicity may also be related to the sleeping habits of the hosts. It has been reported that if the sleeping habits of the hosts are reversed, over a period, the microfilariae change their periodicity from night to day. They are believed to spend the day time mainly in capillaries of the lung and kidney or in the heart and great vessels.

Life Cycle of of Wuchereria Bancrofti:

Wuchereria Bancrofti requires two hosts for completion of its life cycle. Man is the only definitive host and no animal host or reservoir is known for W. bancrofti. The intermediate host is the female mosquito of the genus Culex. The major vector in India and most other parts of Asia is Culex fatigans.

A. In Mosquito:

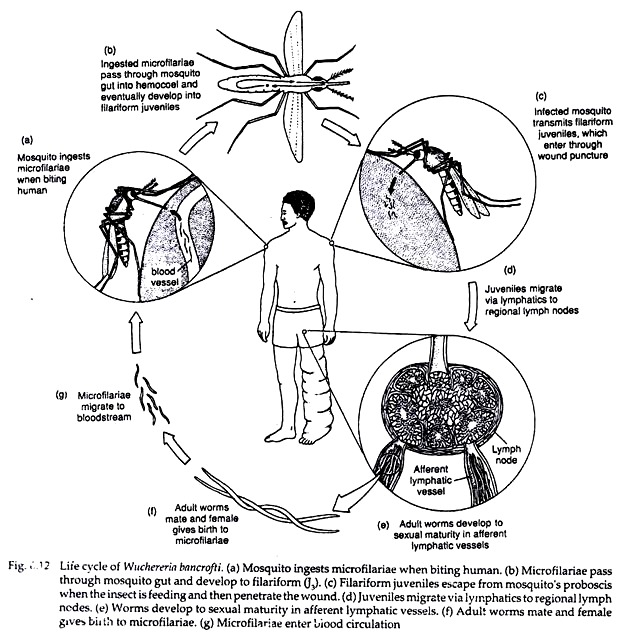

When a vector mosquito feeds on a carrier the microfilariae are taken in with the blood meal and reach the stomach of the mosquito. Within 2 to 6 hours, they cast off their sheath (ex-sheathing), penetrate the stomach wall and within 4 to 17 hours migrate to the thoracic muscles where they undergo further development.

During the next 2 days, they metamorphose into the first-stage larva which is a sausage-shaped form with a spiky tail, measuring 125-250 × 10-15 µm. Within a week, it moults once or twice, increases in size and becomes the second-stage larva, measuring 225-325 × 15-30 µm.

In another week, it develops internal structures and becomes the elongated third-stage filariform larva (J3), measuring 1,500-2,000 x 15-25 µm. It is actively motile and infective. It enters the proboscis sheath of the mosquito, awaiting opportunity for infecting human, the definitive host (Fig. 6.12).

There is no multiplication of the microfilaria in the mosquito and one microfilaria develops into one infective larva only. The time taken from the entry of the microfilaria into the mosquito till the development of the infective third-stage larva located in its proboscis sheath, constitute the extrinsic incubation period.

Its duration varies with environmental factors such as temperature and humidity as well as with the vector species. Under optimal conditions, its duration is 10 to 20 days.

B. In Human:

When a mosquito with infective larvae in its proboscis feeds on a person, the larvae get deposited, usually in pairs, on the skin near the puncture site. The larvae then enter through the puncture wound or penetrate the skin by themselves.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The infective dose for man is not exactly known, but many larvae fail to penetrate the skin and many more are destroyed in the host tissues by immunological and other defence mechanisms. However, it is found that a very large number of infected mosquito bites are required to ensure transmission to man – perhaps as many as 15,000 infective bites per person.

After penetrating the skin, the third-stage larvae enter the lymphatic vessels and are carried usually to abdominal or inguinal lymph nodes, where they develop into adult forms. There is no multiplication at this stage, and only one adult develops from one larva, male or female.

They became sexually mature in about 6 months and mate (Fig. 6.12). The gravid female worm releases large number of microfilariae, as many as 50,000 per day. They pass through the thoracic duct and pulmonary capillaries to the peripheral circulation.

In the peripheral blood, the microfilariae do not undergo any further development. It they are not taken up by a female vector mosquito they die. Their life-span is believed to be about 2 to 3 months. It is estimated that a microfilaria density of at least 15 per drop of blood is necessary for infecting mosquitoes. Densities of 20,000 microfilariae or more per ml. of blood may be seen in some carriers.

Pathogenicity of Wuchereria Bancrofti:

Mode of Transmission:

Filariasis is usually transmitted to man through mosquito biting. The disease can be accidentally transmitted through blood transfusion, when the donor is infected with microfilariae.

Incubation Time:

The period from the entry of the infective third-stage larvae into the human host, till the first appearance of microfilariae in circulation is called the biological incubation period or the pre-patent period. This is usually about 8 to 12 months.

The period from the entry of the infective larvae, till the development of the earliest clinical manifestation is called the clinical incubation period. This is very variable, but is usually 8 to 16 months, though it may often be much longer.

Pathogenesis:

The effects of infection with Wuchereria bancrofti display a wide spectrum from clinically silent infections, with no apparent inflammation or parasite damage, to mild-to-intense non-granulomatous chronic lymphatic inflammation, to a variety of granulomatous obstructive reactions.

Asymptomatic Phase:

Individuals with asymptomatic infections usually have high microfilaremias (a condition of having microfilariae in the blood). It appears that in such people the TH1 type of immune response is down regulated and TH2 type is stimulated. The cytokine IL-4, which suppresses activation of TH1 cells, is elevated and IFN-Ƴ is depressed.

Eventually, after a long period (several years), this tolerance or hypo-responsiveness often breaks down and inflammatory reactions rise.

Thus, two phases of lymphatic filariasis viz:

(1) Hypo-responsiveness, and

(2) Chronic lymphatic disease are initiated by the parasite and immune factors.

A significant proportion of individuals in endemic areas show neither symptoms nor microfilaremia; these are the “endemic normals”. That many such people are actually infected with adult worms can be demonstrated by detection of worm antigen in their blood, although the mechanism of the amicrofilaremia remains unexplained in such cases.

Inflammatory (Acute) Phase:

Inflammatory responses are due to antigens from adult worms, particularly females but not caused by microfilariae. It is now clear that much inflammation is due to invasion by bacteria from the skin surface.

Adult worms in the lymph channels cause dilation of the channels and interfere with lymph flow, resulting in various symptoms which may be described as follows:

(i) Lymphangitis:

Here acutely inflammed lymph vessels may be seen as red streaks underneath the skin. Lymphatics of testis and spermatic cord are frequently involved.

(ii) Lymphadenitis:

This is the repeated episodes of acute inflammation of lymph nodes associated with fever and chills, tenderness along superficial lymphatics. Inguinal nodes are most often affected and axillary nodes less commonly.

(iii) Lymphedema:

This follows successive attacks of lymphangitis, and usually starts swelling around the ankle, spreading to the back of the foot and leg. It may also affect the arms, breast, scrotum, vulva or any other part of the body. Initially the edema is pitting in nature but in course of time becomes hard and non-pitting.

(iv) Lymphorrhagia:

Rupture of lymph vessels leading to release of lymph or chyle.

(v) Filarial fever:

High fever of sudden onset often with rigor, lasting for two to three days that occurs repeatedly at intervals of weeks or months. This fever is accompanied by lymphangitis and lymphadenitis.

Additional common symptoms in the acute stage of filariasis include orchitis (inflammation of the testes, usually with sudden enlargement and considerable pain), hydrocele (forcing of lymph into the tunica vaginalis of the testis or spermatic cord), and epididymitis (inflammation of the spermatic cord).

In such cases, extensive proliferation of living cells with much inflammatory cell infiltration occurs. The most prominent cells include lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils. Abscesses around dead worms may develop with accompanying bacterial infection.

Obstructive Phase:

The obstructive phase is marked by lymph varies, lymph scrotum, hydrocele, chyluria and elephantiasis. Lymph varies are “varicose” lymph ducts, caused when lymph return is obstructed and the lymph “piles up”, greatly dilating the affected duct. This causes chyuria or lymph in urine, a common symptom of lymphatic filariasis.

A feature of the chronic obstructive phase is progressive infiltration of the affected areas with fibrous connective tissue or ‘scar’ formation after inflammatory episodes. However, dead worms are some-times calcified instead of absorbed, usually causing little further difficulty.

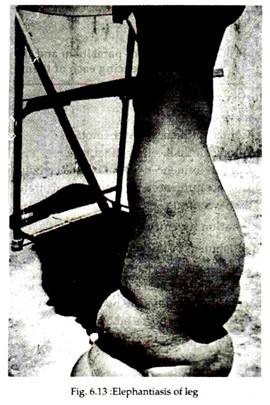

In many cases, repeated attack of acute lymphatic inflammation leads to a condition known as elephantiasis (Ancient Greek and Roman writers compared and described the thickened and fissured skin of infected persons to that of the elephant, though it is a nonsense word, literally meaning “a disease caused by elephant.

But the word is so deeply entrenched, however, that it is not likely ever to be abandoned). This is a chronic lymphedema with much fibrous infiltration and thickening of the skin. In men the organs most commonly afflicted are the scrotum, legs and arms (Fig. 6.13), in women the legs and arms are usually afflicted, with the vulva and breasts being affected more rarely.

The skin becomes thickened due to accumulation of fibrous connective tissues, granulomatous tissue and fat. The skin surface becomes coarse, with warty excrescences; cracles and fissures develop, with secondary bacterial infection. Microfilariae usually are not present in such thickened organs.

Elephantiasis is thus a result of complex immune responses of long duration. After the worms die and are absorbed, the symptoms gradually disappear. Repeated super-infections over many years are usually required for elephantiasis to occur.

Prevention and Control of Disease Caused by of Wuchereria Bancrofti:

The two measures in prevention and control of filariasis are:

(i) Eradication of the vector mosquito, and

(ii) Detection and treatment of carriers.

In endemic areas, insect repellents, mosquito netting and other preventive measures against the vector mosquito (see mosquito control measures) should be adopted. In such areas, peoples (suspected to be carriers) should undergo regular diagnosis for filariasis.

The drug of choice for the past 40 years has been diethylcarbamazine (DEC, Hetrazan) which eliminates microfilariae from the blood and careful administration usually kills the adult. The standard treatment has been 6 mg/ kg doses given over a period (7 to 12 days) to a cumulative total of 72 mg/kg, though this dose has some side effects.

In recent years, it was discovered that a good control could be achieved with a single dose of 6 mg/kg given annually or semiannually; side-effects are fewer and logistics are much easier.

Edematous limbs are sometimes successfully treated by applying pressure bandages, which force the lymph out of the swollen area. Any connective tissue proliferation that might have developed however will not be affected. Surgical removal of elephantoid tissue is often possible.