In this article we will discuss about:- 1. History of Branchiostoma 2. Geographical Distribution of Branchiostoma 3. Habit and Habitat 4. External Structure 5. Body Wall 6. Supporting Structure 7. Locomotion 8. Internal Organisation of the Body 9. Respiratory Mechanism 10. Circulatory System 11. Excretory Organs 12. Nervous System 13. Receptors Organs 14. Reproductive System 15. Development 16. Affinities.

Contents:

- History of Branchiostoma

- Geographical Distribution of Branchiostoma

- Habit and Habitat of Branchiostoma

- External Structure of Branchiostoma

- Body Wall of Branchiostoma

- Supporting Structure of Branchiostoma

- Locomotion of Branchiostoma

- Internal Organisation of the Body of Branchiostoma

- Respiratory Mechanism of Branchiostoma

- Circulatory System of Branchiostoma

- Excretory Organs of Branchiostoma

- Nervous System of Branchiostoma

- Receptors Organs of Branchiostoma

- Reproductive System of Branchiostoma

- Development of Branchiostoma

- Affinities and Systematic Position of Branchiostoma

1. History of Branchiostoma:

In 1974, P. S. Pallas (a German zoologist) first attempted to classify these animals. He named it as Limax lanceolatus and described it as slug. But he had ill-preserved specimens on which he worked. Therefore, this name was rejected.

In 1836 W. Yarrell recognised the special nature of these animals and named it Amphioxus lanceolatus. Later it was discovered that O. G. Costa had christened them as Branchiostoma in 1834. Therefore, by the rules of taxonomic priority, the name Branchiostoma is accepted as generic name and we use Amphioxus as common name.

2. Geographical Distribution of Branchiostoma:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It has almost a cosmopolitan distribution and found on the sandy shores covering the tidal area to depths of many metres. It is an inhabitant of the shores of tropical and temperate seas. The common lancelet, Branchiostoma lanceolatus, has been recorded from the west and southern European coasts, on the East African coasts and also from the western and south-eastern Indian coasts.

3. Habit and Habitat of Branchiostoma:

Branchiostoma lives both in marine and estuarine habitats. It is commonly found in the sandy shores. It lives in dilute sea-water between 15.4% and 33.1% salinities. B. lanceolatus is mostly marine in its distribution and stenohaline (animals restricted to a narrow range of environmental salt concentrations) in its behaviour.

It leads a dual life. It is a sedentary animal although it can swim actively in water. It swims vertically in water. Branchiostoma can swim in water like a fish.

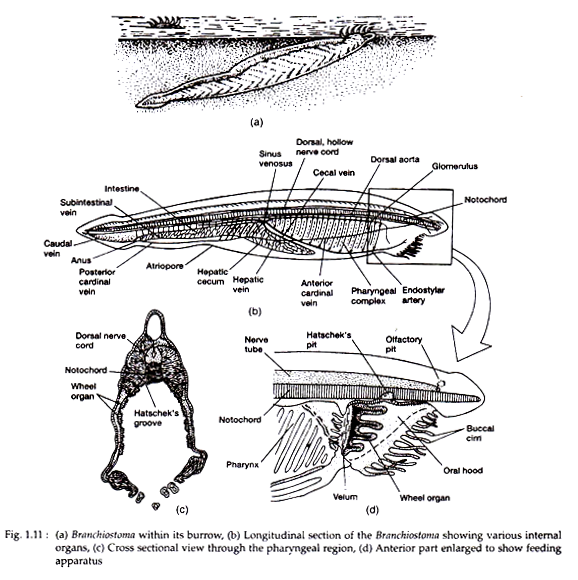

The fins do not play any role during swimming. It burrows in the sand, but remains always at a small depth. It keeps the anterior end of the body projected above the sandy bed to maintain a constant water current passing in through the mouth and expelled through the atriopore (Fig. 1.11).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Branchiostoma feeds on microorganisms brought into the pharyngeal cavity along with the respiratory water current. It exhibits a typical instance of ciliary mode of feeding.

4. External Structure of Branchiostoma:

Branchiostoma is a small lancet-shaped creature with sharply pointed anterior and posterior ends (Fig. 1.11). The length of the animal varies from 5 to 8 cm. The body is elongated and flattened from side to side. The body is distinguishable into the body proper and definite postanal tail. The pointed anterior end projects forward as a snout or rostrum.

Below the snout lies the oral hood formed by dorsal and lateral projections of the body. The oral hood bears more than twenty stiff buccal or oral cirri or tentacles. Mouth is kept hidden within the oral hood and anus is situated on the left side of the ventral fin.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The atrium opens to the exterior through a round atriopore located close to the anterior end of the ventral fin. The sides of the body proper bear numerous gill-slits which remain partly covered by the lateral folds of the body. As a result the gill-slits are not ordinarily seen from outside.

The body is provided with a dorsal median longitudinal fold called dorsal fin. The dorsal fin is joined to a broader caudal fin present around the tail. A ventral fin runs along the mid-ventral line lying between caudal fin and atriopore.

The dorsal and ventral fins are supported by a series of connective tissues called fin-ray boxes. Running along the ventro-lateral sides of the anterior two- third of the body are two longitudinal meta- pleural folds. These meta-pleural folds extend between the oral hood and the atriopore. They possibly help the animal during burrowing in the sand.

5. Body Wall of Branchiostoma:

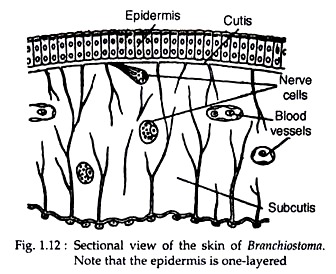

The epidermis consists of a single layer of cells. The epithelial cells are of columnar type (Fig. 1.12). The epithelial layer contains cells with sensory hair (receptor cells), but gland and pigment cells are absent. Immediately beneath the epidermis, there are two layers—cutis and sub-cutis. The cutis is made up of fibres and the sub-cutis has a gelatinous matrix containing fibres. A system of canals traverse through both the cutis and sub-cutis.

Beneath the sub-cutis lies the characteristic muscle layer of Branchiostoma. The mesodermal layer attached with the gut (splanchnopleure), becomes greatly thickened near the notochord to transform into the myotomes or myomeres. Besides the myotomes, other muscles also develop from the splanchnopleure and somatopleure.

The myotomes are blocks of striated muscle fibres extending through the entire length of the body. The myotomes are separated from one another by dense connective tissue septa called myocommas. The myocommas are V-shaped and the pointed end of the ‘V’ is directed towards the anterior end (Fig. 1.11).

Although the myocommas are V-shaped, the muscle fibres composing the myotomes run straight, i.e., arranged longitudinally. Each muscle fibre is attached to two successive myocommas. The myotomes are so arranged that the body can be twisted sidewise with considerable rapidity.

The myotomes on the two sides of the body alternate with one another. Such an arrangement of myotomes helps lateral undulation of the body during locomotion. There are about 60 pairs of myotomes in Branchiostoma.

6. Supporting Structure of Branchiostoma:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The notochord extends from the tip of the head to the tail end. Such anterior prolongation of the notochord beyond the brain is associated with its burrowing habit. This notochord is situated on the mid-dorsal line above the alimentary canal. It is composed of a series of flat plates arranged along the transverse plane of the body.

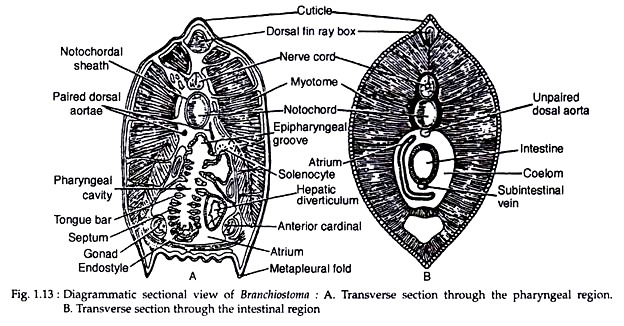

The other supporting structures include the gill-rods supporting the gill-bars, the skeletal oral ring supporting the oral hood and cirri and the fin-ray boxes supporting the fins (Fig. 1.13A).

7. Locomotion of Branchiostoma:

Branchiostoma is a sluggish animal by nature and it occasionally swims freely in water (when it is disturbed) by contraction of the longitudinal muscle fibres of the myotomes. Contraction of the myotomes causes the transverse motion of the body at different angles in such a fashion that the animal can move forward. All the myotomes contract rhythmically along the anteroposterior direction, i.e., a myotome contracts after that in front of it.

During forward propulsion the myotomes contract to produce waves of contraction from anterior to the posterior side through the water. The myotomes are located on the lateral side of the notochord which forms the supporting structure. The function of the notochord is to prevent shortening of the body length when the muscle fibres of the myotomes contract.

The elasticity of the notochord helps to make the contraction of the body more efficient. The notochord acts as the lever upon which the myotomes work. The myotomes have no direct connection with the notochord, but the myocommas are attached with the notochordal sheath.

8. Internal Organisation of the Body of Branchiostoma:

The body proper of Branchiostoma is usually distinguished into pharyngeal and intestinal regions.

In a transverse section through any region of the body proper, the following structures are visible:

1. The outer side of the body is lined by single layered epidermis, with cutis and sub-cutis beneath the epidermis.

2. The sub-cutis is followed by blocks of muscle fibres called myotomes. The myotomes are separated from one another by the myocommas. The myotomes are well-developed on the dorso-lateral sides of the body.

3. A mid-dorsal fin with supporting fin-ray box is present.

4. Immediately above the alimentary canal there lies the notochord which thus occupies a mid-dorsal position.

5. A hollow nerve cord is present just above the notochord.

Besides the common features, there are specific differences between the sections of the pharyngeal and intestinal regions.

The differences is given below:

Comparative account of the transverse section through pharyngeal and intestinal regions of Branchiostoma

Pharyngeal region:

1. Shape− More or less triangular in outline.

2. Ventral fin – two meta-pleural folds are present, one on each ventro-lateral side of the body. Supporting fin-ray box is absent in these folds. These folds contain lymph-filled cavity.

3. Dorsal arota – Two dorsal aortae, one on each dorsa-lateral side of pharynx, are present.

4. Alimentary canal – Pharynx with many gill-bars and section. This is because of the fact that the gill-bars and gill-slits remain diagonal to the body axis. The endostyle and the epipharyngeal groove are present on the mid-ventral and mid-dorsal sides of the pharynx, respectively.

5. Gonads – Paired gonads are seen on the ventrolateral wall of the atrium.

6 Nephridium – Nephridial canal with solenocytes are present.

Intestinal region:

1. Shape− Oval in outline.

2. Ventral fin – Single dorsal mid-ventral fin with supporting fin-ray box is present.

3. Dorsal arota – Single dorsal aorta is present on the mid-dorsal side of the intestine.

4. Alimentary canal – Simple circular intestine with gut content is seen.

5. Gonads – Not present.

6. Nephridium – Not present.

9. Respiratory Mechanism of Branchiostoma:

The wall of the pharynx is highly vascular. The water current entering into the pharyngeal cavity brings fresh oxygen dissolved in water. The gill-bars contain blood vessels with many lateral branches. The blood circulates so close to the surface that these blood vessels are able to absorb oxygen and give off carbon dioxide very efficiently

Since the blood of Branchiostoma lacks any respiratory pigment and also occurs in lymph-spaces in the fins and meta-pleural folds, it is doubtful whether the pharynx has any role in oxygenation. Many workers are doubtful about the respiratory role of pharynx and lay more emphasis on its role in food concentration.

10. Circulatory System of Branchiostoma:

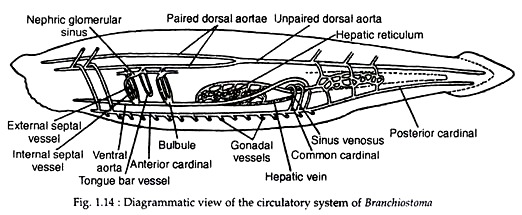

The circulatory system in Branchiostoma is well-developed (Fig. 1.14). Blood is colourless, i.e., it lacks respiratory pigment. Blood is also devoid of cells. It is presumed that the tension of dissolved oxygen acquired by diffusion is sufficient to carry on the vital activities.

Oxygenation takes place in the lacunae situated close to the integument, especially those present in the meta-pleural folds. The blood vessels, except the dorsal aorta, are without any lining.

The blood from the different parts of the body is collected into a large sac called sinus venosus. The sinus venosus is situated below the posterior end of the pharynx. From the sinus venosus a large median artery arises which extends forward below the pharynx. This artery is named the ventral aorta or truncus arteriosus or endostylar artery.

The ventral aorta gives the branchial vessels carrying blood to the gill-bars. The branchial vessel, at the base of each primary gill-bar, dilates to form a tiny expansion called branchial bulb or bulbule (plural bulbuli). From the gill-bars blood is collected by the paired dorsal aortae, situated one on each dorsolateral side of the pharynx.

These paired aortae join posteriorly to form an unpaired median dorsal aorta. This dorsal aorta extends posteriorly up to the tip of the tail as caudal artery. The paired dorsal aortae give small arterial vessels to the nephridia. These vessels form a net of minute vessels called nephric glomerular sinus.

The paired and unpaired dorsal aortae have many branches which lead into the lacunae called myocoel (the space between the myotomes and the body wall). The whole of the intestine and the hepatic diverticulum have extensive blood plexus.

The blood from the tail region is collected by a caudal vein. It proceeds forward to join the sub-intestinal vein. The sub-intestinal vein collects blood from the intestinal plexus. The vein runs into the hepatic diverticulum as the hepatic vein and from there the blood is carried to the sinus venosus.

The blood from the ventrolateral sides of the body wall is collected by two pairs of cardinal veins—the anterior cardinals and the posterior cardinals. The anterior and posterior cardinals of each side unite to form a common cardinal or ductus Cuvieri which passes ventrally to join the sinus venosus.

The sinus venosus, ventral vessel, branchial bulbs, nephric glomerulae and sub-intestinal vein are contractile. The rate of contraction is very slow and occurs once in two minutes. The phenomenon of contraction is irregular and is not controlled by any coordinated system.

The course of circulation of blood in Branchiostoma is as follows:

(1) The blood circulates from the posterior to the anterior end through the ventral vessel, sub-intestinal vein and the posterior cardinal veins.

(2) The paired and unpaired dorsal aortae and the anterior cardinal veins drive blood from the anterior to the posterior direction.

11. Excretory Organs of Branchiostoma:

The excretory organs of Branchiostoma include the nephridia, brown funnels and cells of the atrial wall. The main excretory organs are nephridia.

Nephridia:

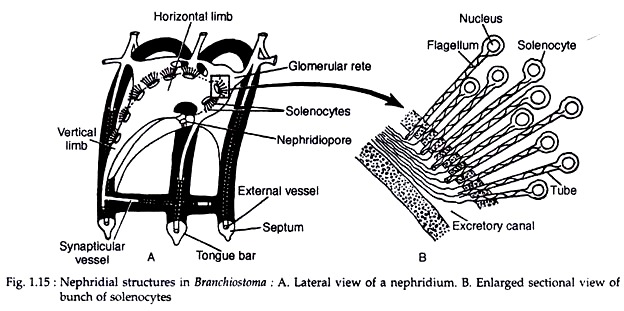

There are about 90 to 100 paired segmental nephridia in Branchiostoma. The nephridia, called protonephridia, are situated on the dorsolateral wall of the pharynx. Each nephridium is a bent vesicular sac having one horizontal limb and one vertical limb. The nephridia are segmentally arranged.

Each sac corresponds to each primary gill-bar and opens by a nephridiopore to the atrium. A large number of elongated tubular flame cells or solenocytes open into the vesicle (Fig. 1.15A). Each solenocyte measures about 50 µm. Each solenocyte has a long tubular stalk with a tiny balloon-like cell-body at the terminal end.

The cell-body gives off a flagellum through the hollow stalk which helps in eliminating the waste products (Fig. 1.15B). The solenocytes become associated with nephric glomerular sinus which separates the solenocytes from the coelomic epithelium.

The basal part of the cells covering the glomerular blood vessels are joined by a membrane. The basement membrane is absent in-between blood and coelomic spaces. Excretion take place through the wall of solenocytes by diffusion and the products pass down into the cavity of the vesicle through the tubular part.

Nephridium of Hatschek:

Besides the nephridia, a tube called the nephridium of Hatschek is regarded to be excretory in function. It arises from the mouth and proceeds forward to the right side of the notochord. It is an ectodermal derivative and gets blood supply from the dorsal aorta.

Miscellaneous Excretory Organs:

Besides the nephridia, the following structures also assist in excretion:

Brown funnels:

A pair of brown funnels are also claimed to play excretory role. These are blind sac-like bodies at the anterior end of the atrium and protrude into the epibranchial coelom. Although these are assigned to be excretory structures by many workers, these are possibly receptor organs.

Atrial wall:

Groups of cells in the atrial wall sub-serve excretory function.

Gonads:

Inside the gonads, particularly in the testes, there are yellow masses containing uric acid. These masses are expelled along with the expulsion of gametes.

12. Nervous System of Branchiostoma:

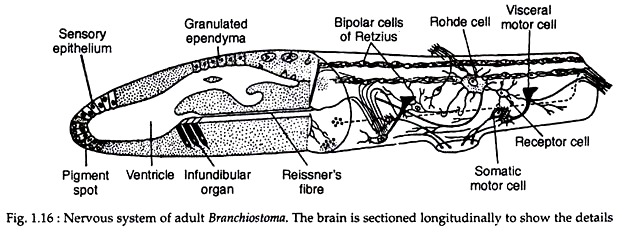

The nervous system of Branchiostoma consists of a hollow dorsal nerve cord situated just above the notochord. The anterior part of the nerve tube is slightly dilated to form the brain and the posterior part remains as the spinal cord. The nerve tube gives paired nerves in each segment of the body. The paired nerves are actually the dorsal and ventral nerve roots which remain separate.

The ventral nerve root lies opposite to the myotome and the dorsal nerve root passes out between the myotomes. The nerves are non-myelinated. The ventral root carries the motor fibres, but the dorsal root is mixed. It carries motor fibres for the nonmyotomic muscles and sensory fibres for the segment.

At the anterior end of the nerve tube, the neurocoel becomes enlarged to form a ventricle. The first two anterior dorsal nerves emerge out from it, but the corresponding ventral nerves are lacking. These two nerves convey the impulses from the receptors of the oral hood and buccal cirri. An infundibular organ is present on the ventral wall of the ventricle (Fig. 1.16).

It consists of tall cells with strong cilia. This organ gives rise to Reissner’s fibre which proceeds posteriorly along the nerve tube. The Reissner’s fibre is comparable to that of the vertebrates. The cells of the infundibular organ contain neurosecretory material as observed in the fibres of the vertebrate hypophysial organ.

In the young stage, the ventricle opens through a neuropore which becomes closed in the adult. The region of the closure is marked by a depression called Kolliker’s pit.

The anterior end of the ventricle contains pigmented cells and sensory cells. Though this organ is regarded by many as photoreceptors, the photoreceptive function of these cells has not yet been experimentally proved. The photo-sensory cells present on the spinal cord are actually the photoreceptors.

The spinal cord has a narrow central lumen and the orientation of grey matter and white matter is similar to that of vertebrates. Scattered in the spinal cord there are photo- sensory cells (eye-spots) enclosed by a cup of pigment granules, the cells of Joseph and Hesse and the giant cells of Rohde (Fig. 1.16).

The cells of Hesse are distributed along the inner side of the tube along the entire length, whereas the cells of Joseph are present anterodorsally. The giant cells of Rohde have many dendrites and one axon. The axon of the anterior giant cells proceeds backward and that of the posterior ones run forward.

13. Receptors Organs in Branchiostoma:

There are various types of receptor organs in Branchiostoma:

(1) Pigment spot:

There is an unpaired pigment spot on the anterior wall of the brain (Fig. 1.16). This spot is usually referred to as cerebral eye which lacks lens and other structures. It is not photosensitive in nature.

(2) Eye-spots:

Photosensitive cells enclosed by a cup of pigment granules (eye- spots) are distributed on the spinal cord and remain oriented in different directions. These are photoreceptors.

(3) Kolliker’s pit:

A ciliated depression at the anterior end of the brain is called Kolliker’s pit. In all probability this is a chemoreceptor. In larval stage its cavity remains in direct communication with the ventricle through the neuropore.

(4) Sensory papillae:

The oral cirri and the velar tentacles are beset with modified sensory papillae which act as the chemoreceptors and tactile receptors.

(5) Infundibular organs:

The infundibular organ (Fig. 1.16), located at the floor of the ventricle, probably acts as photoreceptor.

(6) Epidermal sensory cells:

Sensory cells are present on the surface of the body, especially on the dorsal side.

14. Reproductive System of Branchiostoma:

The sexes are separate in Branchiostoma. The gonads are simple pouch-like segmental organs situated in the ventro-lateral sides of the pharyngeal region between the 10th and 30th segments. The gonoducts are absent and the gametes are discharged into the atrium by dehiscence.

From the atrium the gametes escape to the exterior through the atriopore along with the water current. Fertilisation and development occur in sea water. The eggs are small and isolecithal, i.e., yolk is distributed uniformly in the egg.

15. Development of Branchiostoma:

Primitive, Degenerated and Specialised Features:

Branchiostoma is regarded as an animal organizationally not far from the vertebrate ancestor. It also possesses a mixture of primitive, degenerative and specialised features. In this respect it resembles many other animals.

Primitive Characters:

1. Notochord extends from anterior projection to posterior and persists throughout life.

2. Single-layered epidermis.

3. Myotomic segmentation.

4. The alimentary canal is straight and without loops.

5. The liver diverticulum is simple.

6. Ciliary mode of feeding.

7. Simple circulatory system without a specialised heart.

8. Segmental nephridia which have no coelomoducts.

9. Presence of endostyle.

10. Dorsal and ventral roots of spinal nerves are separate.

11. Gonads are segmentally arranged and without ducts.

12. Absence of biting jaws.

13. Absence of paired fins.

14. Formation of anterior coelomic pouches.

15. Eggs are small and almost yolkless.

16. Blastula is hollow and spherical.

17. Gastrulation embolic.

Degenerated characters:

1. Sedentary in habit.

2. Reduced brain and sense organs.

3. Notochord extending far to the cerebral vesicle.

Specialized characters:

1. Large spacious pharynx.

2. Large number of gill-slits as compared with the body segments.

3. Oral hood, buccal cirri, velum and velar tentacles act as filtering apparatus.

4. Development of atrium reduces and displaces the coelom.

16. Affinities and Systematic Position of Branchiostoma:

Since its discovery, attempts have been made from time to time to determine the biological status of Branchiostoma. A number of groups of animal have been claimed to be related to Branchiostoma. Many non-chordates have been regarded to be phylogenetically related with Branchiostoma.

Relationship with Annelida:

The concept of annelidan relationship of Branchiostoma was mainly sponsored by Dohrn, Semper and Minot.

Similarities:

(i) The body is bilaterally symmetrical and segmented;

(ii) Nephridia are segmentally arranged and are provided with solenocytes;

(iii) Presence of well-formed coelom;

(iv) Similarity in the disposition of the blood vascular system.

Dissimilarities:

(i) In annelids, segmentation is present throughout the length of the body, whereas in Branchiostoma the segmentation is restricted only to the myotomal region;

(ii) The development of coelom is also different. It is schizocoelic in annelids and enterocoelic in Branchiostoma;

(iii) Although the arrangement of the main longitudinal blood vessels is more or less similar in both, the direction of the flow of blood is opposite;

(iv) Branchiostoma possesses all the diagnostic features of the chordates, like the notochord, dorsal tubular nerve cord and gill-slits. None of these three structures are observed in annelids.

Relationship with Mollusca:

The ciliary modes of feeding and respiratory mechanism in Branchiostoma resemble closely that of oysters. At the time of its discovery, Pallas (1778) regarded the specimen to be a slug and named it Limax. The segmentation in Branchiostoma is a very important characteristic, but in molluscs the body is mostly un-segmented. The molluscan locomotor organ (foot) has no parallel in Branchiostoma.

The anatomy of Branchiostoma is completely different from that of molluscs. The superficial resemblances in the feeding and respiratory mechanisms may be interpreted as the result of physiological convergence for similar mode of living and it has no phylogenetic significance.

Relationship with Echinodermata:

The phylogenetic relationship of the Branchiostoma with the echinoderms is rather important. The formation of both coelom and mesoderm is strikingly similar in these two groups. The perforations in the calyx of some fossilized carpoid echinoderms are compared with the gill-slits of Branchiostoma.

Biochemical studies also testify the common ancestry of the two groups of animals. The presence of creatine phosphate during energy transfer in ophiuroids and Branchiostoma, the phosphagens in echinoderms and Branchiostoma are the most important supporting biochemical evidences on this line.

For these reasons the echinoderms were formerly thought to hold the key of chordate origin and the structural similarities of Branchiostoma with the echinoderms were held to be due to inheritance from common ancestry. But, presently, the echinoderms are not regarded as the ancestors of chordates. The similarities are due to a remote common origin of echinoderms and chordates.

Relationship with Vertebrata:

Regarding the relationship between Branchiostoma and the vertebrates, two opposing views may be cited:

(i) Branchiostoma might have evolved from some agnathans by degeneration and

(ii) Branchiostoma is the recent derivative of the ascidians.

The feeding mechanism and larval similarities speak for a close relationship between Branchiostoma and ascidians. Besides these features both of them underwent degeneration and the presence of endostyle establish biochemical relationship.

Branchiostoma possesses many vertebrate features which are lacking in urochordates. Cephalochordates (Branchiostoma as the typical representative) and vertebrates have a common origin from a stock which is separated from urochordate line. Because of remote phylogenetic connection, all these groups are expected to share some common features.

Inclusion of Branchiostoma under the phylum Chordata is universally accepted, because it possesses the basic features of chordate organisation, viz., the notochord, dorsal tubular nerve cord and gill-slits. But its relative status within the phylum is still uncertain.

Relationship with Hemichordata:

The hemichordates and Branchiostoma show many structural similarities. The similarities are:

(1) The pharyngeal apparatus has similar structural construction.

(2) Close similarity in feeding and respiratory mechanisms.

(3) The development and arrangement of coelomic sacs are similar.

These similarities are due to their emergence from a common ancestor. But as regards its relative position, Branchiostoma occupies a higher rank than the hemichordates. In hemichordates the muscles are un-segmented and most of the structures are rudimentary in nature.

Besides, the existence of notochord in hemichordates has been questioned and the nervous system as a whole is built more on non-chordate fashion. Considering all these points, the Hemichordata if at all considered to be chordates must be regarded to be primitive than Branchiostoma from the evolutionary point of view.

Relationship with Urochordata:

The urochordates and Branchiostoma are closely related with one another. The developmental story of urochordates provides the strongest evidence to this view.

The tadpole larva of urochordates resembles Branchiostoma very closely by the following features:

(1) Presence of a continuous notochord.

(2) A hollow nerve cord is located above the notochord.

(3) The pharynx bears endostyle and peripharyngeal grooves.

(4) The tail bears tail fin. The adult urochordates are extremely retro-grated forms. The feeding and respiratory mechanisms are similar.

Most of these structures are evidently homologous and furnish a convincing evidence of closest phylogenetic relationship between the urochordates and Branchiostoma.

Relationship with Cyclostomata:

The ammocoetes larva of lamprey is strikingly similar to Branchiostoma.

Both of them have the following features in common:

(1) Mouth is surrounded by an oral hood.

(2) A velum is present which guards the mouth.

(3) Presence of an endostyle.

(4) Body bears a continuous dorsal median fin. Branchiostoma resembles adult cyclostomes, specially by having myotomes, persistent gill-slits and velum.

But the absence of cranium, vertebral column and paired sense organs in Branchiostoma goes against the view. Because of the similarities, many authors regarded Branchiostoma as a permanent larval form of some species of cyclostomes exhibiting a case of ‘paedogenesis’. But such a view requires more supporting evidences in its favour.