In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Meaning of Communities 2. Types of Communities 3. Characteristics.

Meaning of Communities:

It is now a known fact that individuals of a species together constitute a population. Various places of earth are shared by many coexisting populations and such association is called a community. A generalized definition of community is any assemblage of populations of living organisms in a prescribed area or habitat.

According to A. G. Tansley (1935), community plus its habitat constitutes an ecosystem. In the ecosystem, thus, community and habitat are bounded together by action and reaction. Sometimes ecosystem ecology and community ecology are separated.

Energy flow and biogeochemical cycling are the main features of ecosystem ecology. Although ecosystem represents a broader view than community, still the level of biological integration is the same.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Communities can be identified generally in two ways:

(1) Sometimes communities are recognised from the form of the environment or habitat in which it occurs. For example, communities take their names from physical features such as rock pools, sand dunes etc.

(2) Other communities can be identified by the dominant species in the association. Generally, the most abundant or largest plant species take their names, such as deciduous oak wood, grassland, sphagnum bog communities etc.

Types of Communities:

Kendeigh (1974) divided the biotic community into two types – major and minor communities. Major communities are those that along with their habitats form near complete and self-sustaining units or ecosystems. However, the indispensable input of solar energy is not taken into account.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Minor communities or societies, are not completely independent units as far as circulation of energy is concerned. They are, however, secondary aggregates within a major community. In this text, major communities are generally referred to as communities.

Characteristics of Communities:

Communities, like populations, are characterised by a number of unique properties which are referred to as community structure and community function. Community structure comprises of species richness (types of species and their relative abundances) physical characteristics of the vegetation and the trophic relationships among the interacting populations in the community.

Community function comprises of rates of energy flow, community resilience to troubles and productivity. The structure and function of a community are the manifestation of a complex array of interactions, directly or indirectly tying all the numbers of a community together into an intricate web.

The characteristic features of a community are:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A. Species composition:

A community is a heterogeneous assemblage of plants, animals and microbes. In ecosystems, virtually every organisms of a community, including the most insignificant microbes, plays some role or the other in determining its nature. The species in a community may be closely or distantly related but they are interdependent and are interacting with each other in several ways.

B. Species dominance:

All the species of a community are not equally important. There are a few overtopping or dominant species who, by their bulk and growth, modify the habitat. They also control the growth of other species of the community, thus forming a sort of nucleus in the community.

Some communities have a single dominant species and are thus named after that species, such as sphagnum bog community, deciduous forest community etc. Other communities may have more than one dominant species, for example, oak-hickory forest community.

1. Keystone Species:

There are species upon whom several species depend and whose removal would lead to a collapse of the structure and ultimate disappearance of these other species. Such species are referred to as keystone species, the term coined by Paine in 1966. These species may exert their keystone role in several ways. The beaver is one example whose ponds provide homes for many organisms from pond weeds to black ducks.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Paine through his classic experiments showed that predators and herbivores can manipulate relationships among species at lower trophic levels and, thereby, control the structure of the community. Such predator species are called Keystone predators as their removal can tumble the community. Paine’s work on the star fish, Pisaster ochraceus, is a classical example of keystone predator that feeds primarily on barnacles and mussles (Mytitus).

After removal of this star fish from the experimental areas on the coast of Washington, Paine observed that the mussels spread very rapidly. They crowded other organisms out of the experimental plots, thereby reducing the diversity and complexity of local food webs.

Similarly, removal of the herbivore sea urchin, Strongylocentrotus, allowed a small number of competitive macroalgae to form healthy beds and crowding out limpets, chitons and other bottom-dwelling invertebrates.

2. Direct-Indirect Interactions:

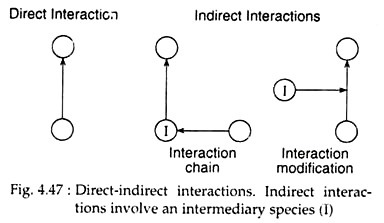

In order to understand the structure of the community, one has to determine which possible interactions are the most important. When direct physical contact of one species with another is involved the interaction is said to be a direct interaction (Fig. 4.47) as in predation, herbivory and parasitism.

When the interaction of one species with another is affected by the intermediance of a third species, then this interaction is called indirect interaction (Fig. 4.47), and this third species is called intermediary species.

Depending on the role of the intermediary species, indirect interaction may result due to two mechanisms:

1. Any indirect effect resulting from a chain of direct effects known as interaction chain.

2. When interaction between two species is affected by the third species (I) is known as interaction modification.

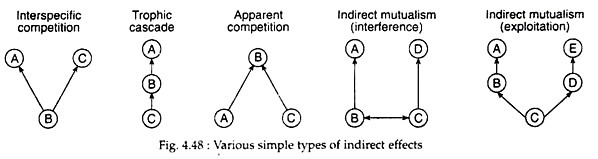

Five simple types of indirect effects may be identified — interspecific competition, trophic cascade, apparent competition and indirect mutualism comprising of interference and exploitation types (Fig. 4.48). Indirect effects are often more complex than what is shown in Fig. 4.48. Even the simple effects are difficult to detect without extensive experimentation.

3. Chemical Interactions among Species:

In a number of cases, species relationships are based on chemical interactions. The study of the production and uptake or reception by organisms of chemical compounds having effects on the organisms is termed chemical ecology. Chemical ecology is not used to include simple relationships, Whittaker and Feeny (1971) put forward a classification based on inter-organismic chemical effects.

They are:

1. Allelochemic effect:

Chemical effects between different species and effects between individuals of the same species.

2. Pheromones:

These serve as chemical messengers between members of a species.

D. Spatial structure:

The members of a community exhibit a spatial structural pattern.

Structurally, communities may be divided into the following types:

1. Communities may be divided horizontally into sub-communities. They constitute the zonation in a community.

Examples:

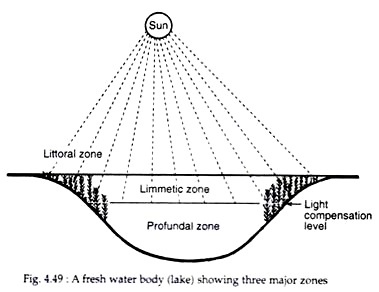

(i) In deep ponds and lakes three zones (Fig. 4.49) may be recognised-upper littoral zone, middle limnetic zone, and a lower pro-fundal zone. Each zone constitutes different types of organisms. However, shallow ponds have very little zonation.

(ii) Mountains show zonations of different distinct vegetational type. Altitudinal zonation in a mountain is due to climatic variations.

2. Another aspect of structure is stratification—which is very common. Ecosystems generally have noticeable vertical structure (strata).

Examples:

(i) Many ecosystems show two broad tropic strata – upper autotrophic and lower heterotrophic. In the upper part of the water of a lake, food production is restricted up to the part where light penetrates. The bottom of the lake comprises of heterotrophic organisms (animals and bacteria) that depend upon the autotrophs of the upper strata.

Similarly, in a forest ecosystem, food-making activities take place in the upper part where the leaves are concentrated, while consumption and decomposition occur on or beneath the forest floor.

(ii) Some community may comprise of more than two strata. Some forests-like a complex deciduous forest community-shows stratification where five vertical sub-divisions of different vegetational types are present. These vertical subdivisions are — sub-terranean, forest floor, herbs, shrubs, and trees.

(iii) Some communities may lack some of the above strata or may have other strata comprising of the same group of vegetation. Bog forests have two strata of herbs, a lower strata of plants like partridgeberry and gold thread and a higher strata of skunk cabbage leaves and ferns. Tropical rain forests may have three tree strata, while the herb and shrub layers are poorly developed.

3. Instead of occurring in zonation or strata, organisms may divide the habitat in a more complex manner by just occurring in layers.

Example:

In the Ponderosa pine forests of Colorado during winter, three different species of nuthatches live together. The familiar white-breasted nuthatch are generally seen scrambling in crevices in the bark of a tree in search of food A second slightly smaller species, the red-breasted nuthatch, obtains its food by foraging on large branches of the trees.

A third, much smaller species, the pigmy nuthatch, gets its food from small branches and clusters of pine needles. The above example shows division of resources as they occupy different ecological niches. This probably reduces interspecific competition.

4. In aquatic communities, temperature may cause thermal stratification.

Example:

Large lakes and oceans, depending on the temperature, are formed of three layers — upper epilimnion, a middle thermocline (Metalimnion), and a lower hypolimnion.

E. Community periodicity:

Periodicity refers to the rhythmic activity of an organism for food, shelter and reproduction. The periodicity of a community is related to seasonal changes, day and night, lunar rhythms, and the inherent property of the animals.

(a) Day-night changes:

The daily periodicity is due to the occurrence of day and night. Accordingly, organisms that are active in the daylight hours and inactive (sleep) in the night are diurnal, while those active at night and inactive at day are nocturnal. A few organisms are either active at dawn or dusk or at both the times — they are said to be crepuscular.

Most crepuscular animals like the whippoorwill, show increased activity mostly during bright moonlight. Some nocturnal animals like bats and moths are lunar phobic that is they become less active during bright moonlight.

There are other 24 hour cycles occurring in organisms such as daily patterns of physiological activity like production of new cells or the secretion of a particular enzyme. Many cycles like wakefulness, locomotion etc. persists even in environments with no alternation of light and dark.

Such daily cycles are called circadian rhythms. Why are organism nocturnal or diurnal? There is no single evolutionary answer. The evolving of nocturnal animals may be due to high humidity at night or evading diurnal predators or competitors.

(b) Seasonal changes:

Many communities show seasonal changes in structure, appearance and function, depending on the changes in seasons.

Example:

1. The most marked are the seasonal changes in temperate deciduous forests, where changes are seen during six recognisable seasons.

2. In many tropical and subtropical ecosystems, wet and dry conditions are more important than warm and cold seasonality. This is true in case of Sonora desert, monsoon forests etc.

3. Hot springs generally have constant temperature and salinity. They show changes during seasonal differences in sunlight.

F. Synusia and Guild:

Synusia, the term coined by DuRietz in 1930, denotes the subdivision of a plant community consisting of all the plants of the same life form. They also correspond to the layers of the community, like the canopy trees of a forest or the mosses of a bog. In a tropical rain forest, the larger epiphytes form a synusia and the epiphylls, that is the algae and lichens that grow on rain forest leaves, form another.

Guild, the term put forward by Root in 1967, presents a group of species that exploit the same classes of environmental resource in a similar way, or, in other words, they eat similar foods. The frugivores of a tropical rain forest feed on the fruits and are thus considered as guild.

Similarly, insects feeding on broad-leaved trees form one guild. Studies have shown constancy in the proportion of total species in certain guilds within a community. This is true in the case of the ratio between the predator species and prey species. This indicates that there might be certain common rules that govern community structure.

G. Eco-tone and Edge effect:

Communities generally have their boundaries well-defined. The intermediate zone lying between two adjacent communities are called eco-tones. The border between a forest and a grassland, the bank of a stream running through a meadow, an estuary (the junction where the river meets the sea), the transition between aquatic and terrestrial communities, between distinct soil types, are a few examples of eco-tone.

Even the transition between north-facing and south-facing slopes of mountains is eco-tones where the transition between communities is abrupt and obvious. The eco-tone may be as broad as 100 kms or as narrow as 1 km. Species are distributed at random in respect to one another giving an open structure.

The environmental condition in an eco-tone is variable, intermediate between the two adjacent communities. Boundaries between grassland and scrubland or between grassland and forest have sharp changes in surface temperature, soil moisture, light intensity and fire frequency. This results in replacement of many species.

Grasses prevent the growth of shrub seedlings by reducing the moisture content of the surface layer of soil. Shrubs, on the other hand, depresses the growth of grass seedlings by shedding them. The edge between prairies and forests in mid-western United States is maintained by fire. Perennial grass resists fire damage to tree seedlings.

Eco-tone generally offers an abundance of food and shelter. It contains organisms from both the communities. As a rule, eco-tone contains more species and often a denser population than the two concerned communities. This is called edge effect. There are certain species which are entirely restricted iii the eco-tone and are called edge species.

However, it must be made clear at this point that the concept of eco-tone is not restricted to the interaction among communities, nor to the transition in the number of species. Eco-tone may be viewed as a surface forming common boundary between populations, or between ecosystems, as well as between communities. Eco-tone transitions will include fluxes of materials as well as transition in number of species.

H. Habitat and Ecological niche:

The word habitat is used to denote where an organism lives, or the place where one would go to find it. The word habitat is a Latin word which literally means ‘it inhabits’ or ‘it dwells’. It was first used in the eighteenth century to describe the natural place of growth or occurrence of a species. For example, the lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla) has as its habitat lowland tropical secondary forest.

Hericium abietis (fungus) habitats on coniferous logs and trees in the Pacific, northwest of USA. Some species, like the tiger (Panthera tigris), have several habitats. It includes tropical rain forest, snow-covered coniferous and deciduous forests and mangrove swamps.

The habitat of some smaller organisms is highly specialised. Certain species of leaf miners live only in the upper photosynthetic layer of leaves, while other species live in the lower cell layer in certain plant species.

Thus, the habitat of the two species is different and such divisions of the environment are called microhabitats. Any one environment is divided up into many possibly thousands of microhabitats. The specific environmental variables in the microhabitat of a population is called micro- environment or microclimate.

The term niche is used by ecologists to express the relationship of individuals or populations to all aspects of their environment. Niche, thus, is the ecological role of a species in the community. It represents the range of conditions and resource qualities within which an individual or species can survive and reproduce. Niche is multidimensional in nature.

Distinction between habitat and niche:

The words habitat and niche are often misunderstood. At this stage it is important to distinguish between the two terms in ecology. A habitat is a description of where an organism can be found, but its niche is a complete description of how the organism relates itself to its physical and biological environment.

For example, the habitat of the back swimmer (Notonecta) and the water boatman (Corixa) is the shallow area of ponds and lakes. They, thus, occupy the same habitat. However, the two species occupy very diversified trophic niches. The backswimmer is an active predator, whereas the water boatman feeds largely on decaying vegetation. Although species coexist they use different energy sources.

The habitat is the address of the organism, while niche is its ‘profession’, that is its trophic position in food webs, how it lives and interacts with the physical environment and with other organisms in its community. Habitat refers not only to organisms, but it also refers to the place occupied by an entire community.

The habitat of the sand sage grassland community occurs along the north sides of rivers in the Southern Great Plains of the United States. Thus, from the examples of the above, it can be said that the habitat of an organism or groups of organism (population) includes other organisms and the abiotic environment.