In this article we will discuss about the parental care in fishes.

Many species of fishes do not care for their eggs and fingerlings. They leave the spawning grounds after fertilization. For such species of fishes the lacking parental care behaviour is compensated by the production of large number of eggs. Such fishes lay over 300 million eggs at a time.

The cod fish lays over nine million eggs which are scattered at random in the open sea. Carps lay two to four million eggs at random in fresh water and adjoining aquatic vegetation. It has been estimated that about 77 percent fishes show no parental care, another 17 percent of the fish species care for the eggs only, while less than 6 per cent care for eggs and newly hatched young.

Fishes that produce limited number of eggs have evolved various grades of parental care behaviour:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A. Deposition of eggs in suitable places.

B. Deposition of eggs into self-made nest.

C. Concealing eggs and young’s in or on their body.

D. Viviparity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

E. Care of independently swimming young’s.

A. Depositing Eggs in Suitable Places:

A number of fish species have developed some design of depositing their eggs in suitably protected places. They do not build nests.

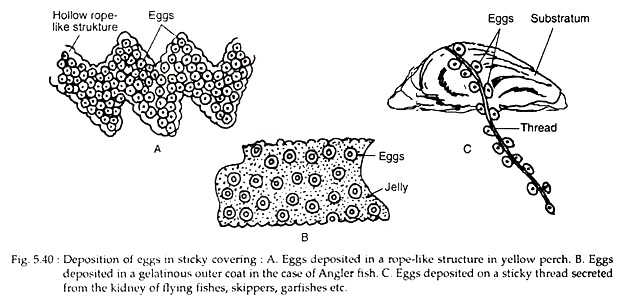

(a) Deposition of eggs in sticky covering:

(i) In carps, eggs are usually laid with some special sticky covering by means of which they are attached to each other or to stones, weeds etc.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) In yellow perch (Perca flavescens) eggs are deposited in a rope-like structure (Fig. 5.40A). The eggs are held together by a long floating membrane.

(iii) Angler fish (Lophius) lay their eggs invested by a gelatinous external coat, that remain together to form a transparent mass of enormous size (Fig. 5.40B).

(iv) Flying fishes, skippers, garfishes etc. secrete a sticky thread-like substance from their kidney, on which the eggs remain attached (Fig. 5.40C). The thread on one end remains adhered to any aquatic substratum while the other end remains free.

(b) Eggs scattered over aquatic plants:

Eggs of fishes such as pikes (Esox lucius), carps (Cyprinus carpio), Carrassius auratus etc., are scattered over aquatic plants to which they remain attached.

(c) Eggs layed at suitable places:

(i) Anadromous fishes (lives in the sea but migrates to fresh water for breeding) such as Salmo solar, Acipenser, Oncorhyncus etc., lay their eggs in suitable spawning grounds. They dig excavation in gravel substrate, lay their eggs in the pits, cover them with gravel and desert them.

(ii) Sand Gobi (Pomatoschistos minutus) lay their eggs in some protected place, where they are guarded by the male who also aerates them by his movement.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

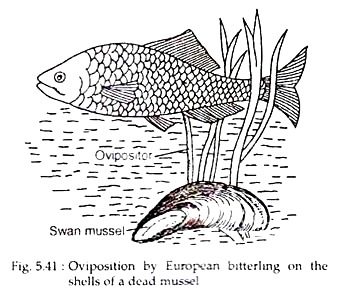

(d) Eggs deposited on dead shells of bivalves:

(i) Females of cyprinid family deposit their eggs on the dead shells of mussels.

(ii) Females of European bitterling (Rhodeus amarus) deposit eggs in the siphon of a fresh-water mussel by means of a long tube acting as an ovipositor (Fig. 5.41). This ovipositor is a long tube drawn out from the oviduct.

After oviposition male Rhodeus immediately sheds the sperm over the eggs and then guards them. The male Rhodeus, interestingly, are not sexually excited by the presence of the female of its own species, but by the sight of the shell of the mussel in which the eggs have been deposited.

B. Deposition of Eggs Into Self-Made Nest:

Some species of fishes prepare nests of different types for the safe deposition and protection of eggs, and for the development of their young ones. In the building of the nest, only the males or both sexes participate. Various kinds of materials such as pebbles, aquatic vegetation, secretion of their body etc., are used for nest formation.

The different types of nests built are:

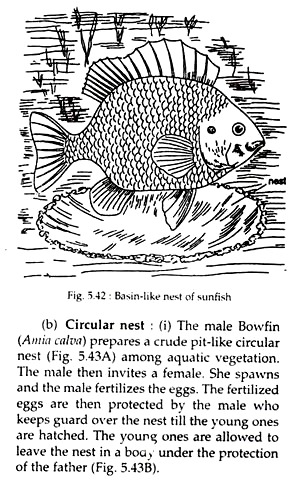

(a) Basin-like nests:

(i) Male of Darter (Etheostoma congregata), during the spawning season, selects a suitable place called domain, which it defends repelling with vigour any attempt by rival males. Any female Darter entering its domain is allowed to remain.

The female Darter then makes a basin-like depression, sinks into it and deposits the eggs. The eggs are immediately fertilized by the male who covers the fertilized egg by a sticky secretion, secreted from its kidneys. These sticky eggs remain attached to the stone till hatching.

(ii) Fresh water sunfishes build a nest by scooping out a shallow basin-like nest at the bottom of the impoundment by carefully removing pebbles and leaving behind large stones (Fig. 5.42). A layer of fine sand remains attached with the eggs. Male sunfish guard the eggs till they hatch.

(iii) Cichlid fishes (Haplochromis burtoni) build basin-like nest which is guarded by both the parents.

(iv) In some North American catfishes both the male and female prepare a crude nest in the mud to lay eggs.

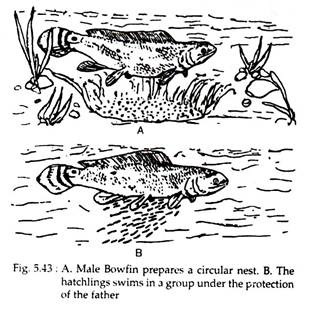

(b) Circular nest:

(i) The male Bowfin (Amia calva) prepares a crude pit-like circular nest (Fig. 5.43A) among aquatic vegetation. The male then invites a female. She spawns and the male fertilizes the eggs. The fertilized eggs are then protected by the male who keeps guard over the nest till the young ones are hatched. The young ones are allowed to leave the nest in a boa/ under the protection of the father (Fig. 5.43B).

(ii) Both the male and the female of some cat fishes (Arius) of North America prepare a crude circular nest in the mud, at the bed of the river. The diameter of the nest is about 50 cm and is sometimes provided with a protective cover of logs, stones etc. The fertilized eggs are left uncared.

(c) Hole/Burrow nest:

(i) The African lung fish (Protopterus) prepares a simple nest in the form of a deep hole in swampy places along the river bank. The male prepares the nest surrounded by long aquatic weeds and grasses and after spawning keeps guard over it, occasionally aerating the water by his slow body movement.

(ii) The South American lung fish (Lepidosiren) prepares a nest in the form of a burrow in swampy places, varying in length from 1 to 2 metres. The nest consists of a short vertical and a larger horizontal portion in which eggs are deposited. Males take care of the eggs. During this time they develop a long red filament from the pelvic fins which perform the function of aeration without coming out on to the surface to gulp air.

(d) Barrel-shaped nest:

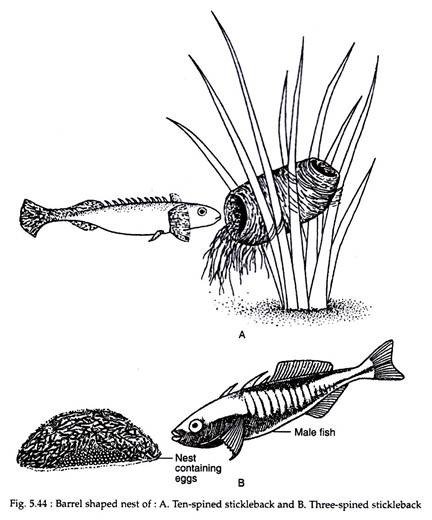

Before the start of courtship the male stickleback (example: three-spined stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus and ten-spined stickleback, Pygosteus pungitius) builds a quite elaborate nest. The male at first selects suitable place in shallow water where the flow of water is continuous but not swift.

He then builds a nest by collecting plant fragments, rootlets, weeds and then binds them together with the help of a sticky secretion from its kidney. The various activities of males such as probing, boring, sucking and glueing result in the formation of a compact nest with tunnel to receive the eggs (Fig. 5.44).

The male then goes out in search of a mate. The bulging abdomen of the female stimulates the male to perform a zigzag dance around her, displaying his red spot. If the female is ready to lay eggs she responds by curving her head and tail upwards. On reaching the nest the male opens the entrance of the nest with its snout. The female, after depositing two to three eggs within the nest, swims out of the nest through the opposite side of the entrance.

The male then enters the nest and fertilizes the eggs. He then comes out of the back entrance and moves out to seek another female. The same process is then repeated till sufficient eggs are deposited. The male then guards the nest and keeps the eggs aerated by fanning the nest with his fins and tail. Later, the male stops fanning and keeps close watch over the brood, not allowing any young one to go astray.

(e) Cup-shaped nest:

The male of Apelts quadracus builds an elaborate cup-shaped nest, attached to rooted plants close to the bottom. After a female lays a clutch of eggs, the male builds an extension of the nest up and over the eggs, with a concave upper surface in the extension. A second female lays another clutch of eggs on the new concave floor. This process is repeated several times, until the male has several clutches of eggs stacked vertically within a multi-tiered nest.

(f) Floating nest:

The male Mormyrids (Gymnarchus) constricts a floating nest with the help of aquatic vegetation. The wall of the nest remains projected several centimeters above the water surface.

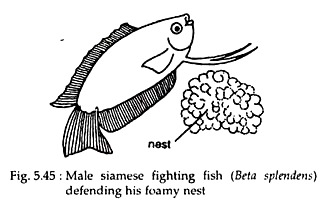

(g) Foamy nest:

(i) The nest made by American catfishes contains eggs that are suspended in a mass of bubbles and mucus produced by the male.

(ii) The male fighting fish (Beta) builds a nest by blowing bubbles of air and sticky mucus that adhere together forming a floating mass of foam on the surface of water (Fig. 5.45). The fertilized eggs are collected by the male in his mouth, who gives them a coating of mucus and sticks them to the lower surface of the foamy nest. The male then stays on guard and fights till death to defend it.

(iii) The male paradise fish (Macropodus), also prepares a similar foamy nest. In this species the eggs are lighter and rises up to the nest without the active participation of the father.

C. Concealing Eggs and Young’s in or on their Body:

Certain species of fishes have developed many structures in their body to safeguard the eggs and young ones:

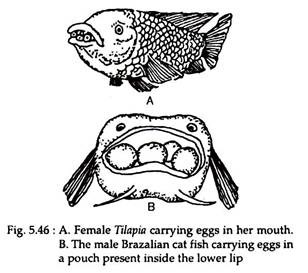

(a) Eggs and young’s concealed in mouth cavity:

(i) In many cichlids (Example: Tilapia), the female broods the fertilized eggs in her mouth (Fig. 5.46A). After hatching she allows the young to take refuge in her buccal cavity in times of danger.

(ii) In most marine cat fishes (Arius) and cardinal fishes, the male carries the eggs and young ones in his mouth. The male does not take food during this period.

(iii) In case of the Brazilian cat-fish (Loricaria typus), the male has an enlarged lower lip forming a sort of pouch in which labial incubation takes place (Fig. 5.46B). This ensures safety and provides perfect aeration. During this act, the male fish do not take any food. Even after hatching the hatchings remain near the father and enter the buccal cavity of father at the slightest disturbance.

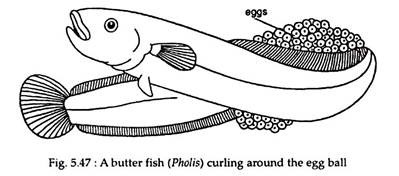

(b) Formation of egg ball: The butter fish (Pholis) rolls the eggs into a round ball and then one of them remains on guard by curling around it (Fig. 5.47). It is often the male that guards the egg ball till hatching of young.

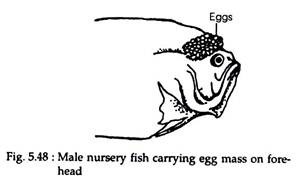

(c) Eggs attached to cephalic hook:

The male nursery fish (Kurtus) of New Guinea, carries the mass of eggs on the forehead, held in a cephalic hook (Fig. 5.48).

(d) Eggs in integumentary cups:

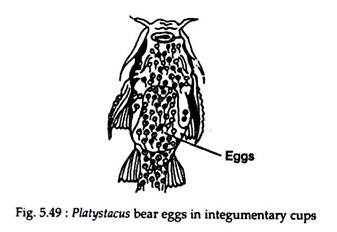

The cat-fish, Platystacus of Brazil, shows an interesting method of parental care. During the breeding season, the skin of the lower surface of the body of female becomes soft and spongy. Immediately after the eggs are fertilized, the female presses her body against the eggs in such a manner that each egg becomes attached to the skin by a small, stalked cup (Fig. 5.49). The eggs remain fixed in this position till hatching.

(e) Eggs kept in brood pouches:

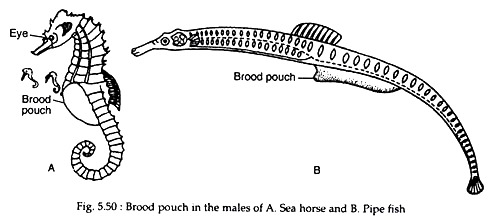

(i) In sea horse (Hippocampus) fertilized eggs are transferred by the female into the brood pouch (Fig. 5.50A) of the male. The brood pouch is found on the lower surface of the abdomen. During the males so called ‘pregnancy’, he provides nutrients and oxygen to the fertilized eggs for several weeks.

Generally, a single large female produces enough eggs in one cycle to fill the brood pouch of nearly three large males. As the sex ratio is 1 : 1, male pouches are in short supply. Thus, males exhibit active mate choice. They favour large ornamental ones that can fill their brood pouch with eggs quickly and sufficiently. After hatching, fry may return to the pouch when in danger,

(ii) In the male pipe-fish (Syngnathus), a brood pouch (Fig. 5.50B) is formed by two flaps of skin on the underside of the body on which eggs are placed by the female.

(iii) In the family solenostomidae, pelvic fins of females form the brood pouch. The eggs inside the brood pouch are kept in proper position by numerous long filaments.

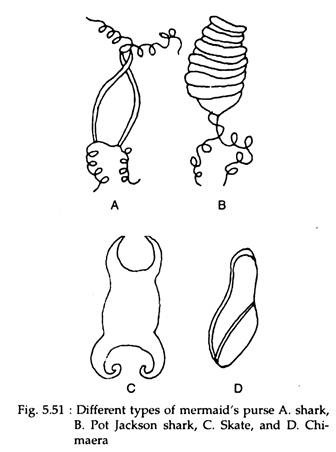

(f) Egg capsules:

In oviparous elasmobranchs such as sharks and rays, the fertilized eggs are laid inside protective Horney egg capsules called mermaid purse. The shape of the purse varies in different groups (Fig. 5.51). The capsules remain attached to aquatic weeds by their tendrils. The development of the eggs is completed inside the purse.

D. Viviparity:

The highest degree of parental care is exhibited by those species which are viviparous. They have evolved internal incubation and give birth to young ones, thereby providing maximum protection.

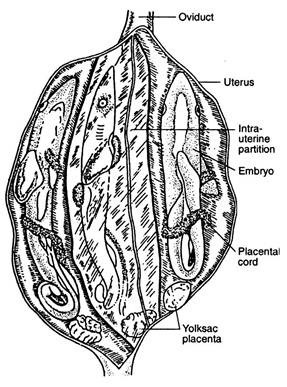

(a) Viviparous Elasmobranchs:

Among the sharks, viviparity has been witnessed in more than a dozen families. In case of Scoliodon, Mustelus etc., eggs develop in the uterus. The mucous lining of the uterus forms fluid-filled protective compartments, one for each embryo. Nourishment in the form of embruotrophe or uterine milk is received by each embryo from the uterine tissue through the yolk-sac placenta (Fig. 5.52).

(b) Viviparous Bony Fishes:

(i) In teleosts, species (Example: Zoarces, Gambusia and Poicilia) belonging to the orders Cyprionodonts and Perciformes show internal fertilization and the young ones develop within the ovary but are not attached to its wall.

The embryos develop freely in a sac inside the ovary, feeding upon an “embryotrophic” material, apparently produced by the discharged ovarian follicles. The sac becomes highly vascular and remains as such during the months of pregnancy.

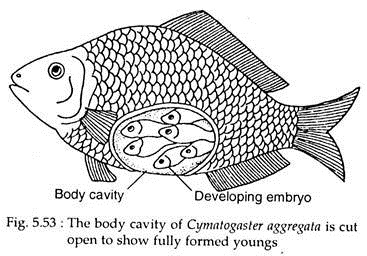

(ii) In the case of shiner-perch (Cymatogaster aggregata) the eggs also are fertilized in the ovarian follicles, but are soon released into the ovary cavity and are nourished by a secretion from the ovary (Fig. 5.53). The young are retained in the ovary until they become sexually matured.

(c) Ovo-viviparous:

An intermediate condition between oviparous and viviparous is observed in the case of nurse shark (Gingly mostoma), called ovo-viviparous. Here the eggs are covered by a horny case and the development takes place in the uterus. The fully developed young ones hatch out by breaking the shell inside the uterus.

E. Care of Independently Swimming Young’s:

In the members of some families such as Gasterosteridae, Centachidae and Ictaluridae, parental care does not stop with the caring of the eggs. These fishes defend their young ones by placing them in a safe place, away from predators and enemies.

As has been dealt with earlier, the young ones of Tilapia, seahorse and pipe fish are protected by their parents either in the oral cavity of mother or in the brood pouch of the father. In the case of cichlid fish, both male and female secrete a nutritious substance from their body, which are taken up by their young ones.