The following points highlight the three main types of teeth found in mammals. The types are: 1. Incisors 2. Canines 3. Cheek Teeth (Premolars and Molars).

Type # 1. Incisors:

These are the front teeth borne by the premaxillae in upper jaw and tips of dentaris in lower jaw They are single-rooted, monocuspid and long, curved and sharp-edged. They are adapted for seizing, cutting and biting (Fig. 33.2).

Incisors are sometimes totally absent as in sloths; sometimes they are partially absent and in the upper jaw of many artiodactyles (cow, giraffe), where the incisors of the lower jaw bite against a callous pad in the corresponding region of the upper jaw. The incisors are small in carnivorous animals (cat, tiger, dog), where they are used in a limited way. In the insectivorous mammals the upper and lower incisors are elongated and work like a pair of forceps to catch hold of the active prey.

In rodents (squirrel and rat) and lagomorphs the incisors assume great functional importance in that they are constantly used for gnawing at hard-vegetable matter. The gnawing incisors of such animals are rootless and can, therefore, grow throughout life, thereby compensating for rapid wear. In such cases only the anterior surface of the incisor is covered with enamel.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The incisors of the two jaws oppose each other and are kept sharp by whetting against each other, since the dentine wears away more rapidly than the harder enamel. The tusks of the elephant also are rootless incisors. In some elephants (Loxodonta) the enormous up-curved tusks measure about eleven and half inches (11.5 inches) and weigh nearly 350 pounds. The tusks are composed of hard dentine except for temporary cap of enamel at the tip. In lemurs, incisors are denticulate like a comb, serving for cleaning fur.

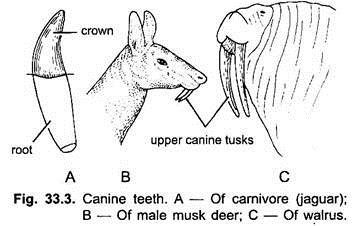

Type # 2. Canines:

Canines are present in the majority of mammals. They always have conical pointed elongated single rooted crowns and are used for piercing and tearing. A single canine tooth occurs in each half of each jaw, just outside the incisors. Upper canines are the first teeth on maxillae.

In carnivorous animals the canine teeth assume great functional importance. In such animals they tend to become larger and much stronger to serve an efficient organs for piercing and tearing the flesh of the prey. In walruses only the upper canines develop into enormous offensive tusks.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the herbivorous animals, on the other hand, the canines are of relatively less importance and, if present, they are much less developed than those of carnivores. In some of the artiodactyla (cow and giraffe) the canines are absent only in the upper jaw. They are entirely absent in both jaws of all rodents (rats), elephants and dugongs.

In the males of some forms (apes) the canines (as also the first molar) are decidedly larger than those of the females. The tusks of male boar are greatly developed canines, with large persistent pulp cavities. In other forms such as the musk deer the canines are present only in the upper jaw of males. It may be said that these animals exhibit sexual dimorphism with respect to dentition. Canines are absent in some herbivores such as rodents (rats), lagomorphs (rabbits) and some ungulates (ox) leaving a wide toothless space called diastema.

Type # 3. Cheek Teeth (Premolars and Molars):

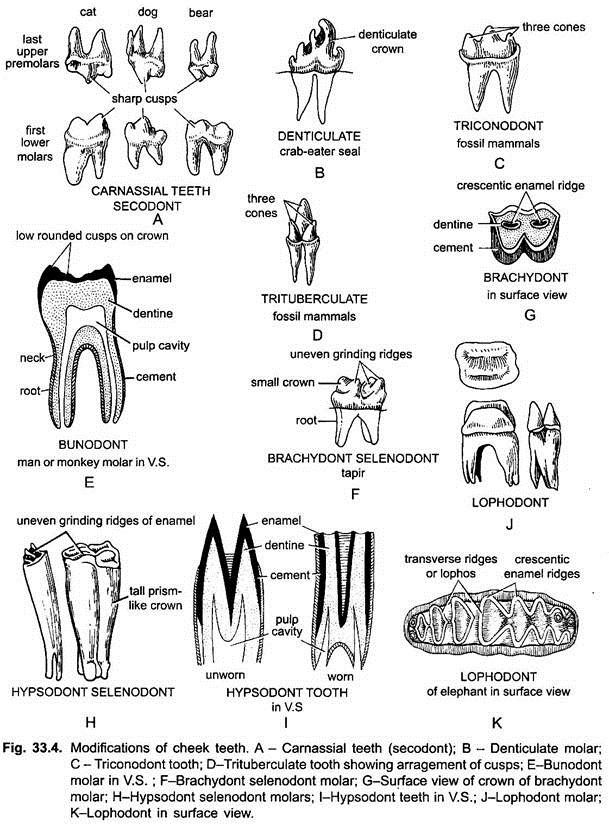

Canines are followed by premolars followed by molars. Both types are collectively called cheek teeth. Their crowns have broad surfaces with ridges and tubercles meant for crushing, grinding and chewing. Premolars usually have two roots and two cusps and are represented in milk dentition. Molars generally have more than two roots and several cusps and do not have milk predecessors (Fig. 33.4).

The cheek teeth or the grinding teeth are the teeth which show the greatest amount of variation in their form and structure. This is shown by the variety of the number and arrangement of cusps and ridges at the apex of the crown. The number of cusps of a cheek teeth may vary from one to many.

In carnivores, last premolars in upper jaw and first molars in lower jaw may have very sharp cusps for cracking bones and shearing tendons. These are called carnassial teeth. In lemurs, first premolars are like canines. In crab-eater seal molars bear denticulate processes to strain plankton. In higher primates (man), last molar is called wisdom tooth. Its emption may be delayed, or it is imperfectly formed or absent in man.

Types of Cheek Teeth:

Cheek teeth are of various types depending on the number, shape and arrangement of cusps.

These are of the following types:

1. Triconodont:

These are found in fossil Mesozoic mammals in which 3 cones are arranged in straight line or linear series.

2. Trituberculate:

These are found in fossil mammals in which 3 cones or tubercles are arranged in the form of a triangle.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Bunodont:

These are found in mammals with a mixed diet such as man, monkey, pig, etc. Their crowns bear small separate blunt and rounded tubercles meant for crushing.

4. Secodont:

This condition is found in terrestrial carnivores and in insectivorous mammals in which teeth have sharp cutting edges or crowns for tearing and cutting flesh.

5. Selenodont:

This condition is found for grinding in herbivorous ruminating mammals such as cow, horse and others in which cheek teeth have vertical crescent-shaped folds of hard enamel enclosing softer areas of dentine with cement filling interstices.

Normal low crowned selenodont teeth with short roots (ground squirrel) are termed brachydont. In large grazing mammals such as horse and cattle, teeth are elongated, prism-shaped with high crowns and low roots. This condition is known as hypsodont.

6. Lophodont:

This condition is found in elephants which feed on very hard vegetable matter, enormous grinding teeth are present which may be long and about 10 cm wide. In these teeth there is an intricate folding of enamel and dentine to form transverse ridges or lophs. The spaces between lophs are filled with cement.

A single large lophodont molar, 30 cm by 10 cm, is present at one time in each half of each jaw. These are adapted to grind all sorts of plants, including grasses. In elephants as well as manatee, there is a constant succession of teeth from behind throughout life. The front ones are pushed forward and are shed as new ones from behind.

Only one fully developed tooth is present at any one time on each side of each jaw in elephants. The shape and disposition of the ridges varies in the Indian and African elephants; in the former (Indian elephants) they are many and are more or less parallel to each other, while in the later (African elephants) they are few and diamond-shaped.

In some of the ancient mammals the selenodont and bunodont types are mixed and such teeth are termed bunosalenodont. In others the bunodont and lophodont types are blended into the bunolophodont condition.

The functional adaptation of the dentition of some mammals such as Ornithorhynchus (duck-billed platypus), and cetaceans deserve special mention. In Ornithorhynchus true teeth are absent in the adult; their places are taken by horny plates which are suited for crushing the prey Among the living Cetacea conical, calcified, homodont teeth are present only in the toothed whales (Odontoceti).

In the sperm whale they are present only in the lower jaw and are not lodged in sockets but set in grooves. In the dolphin, numerous homodont teeth are present in both jaws. In these toothed cetaceans, which feed mainly on fishes, the teeth are recurved and serve only to hold the prey and prevent it from escaping. But in the adult whalebone whale, which feeds only on the plankton, teeth are entirely absent; of these whalebone whale have what is known as whalebone (or baleen) hanging from the palate.

Theories about the Evolution of Molars:

The origin of complex cheek teeth in mammals have been a controversial issue. Two main theories have been proposed to explain the evolution of the molars; one is the Concrescence theory of Rose and the other is the Tritubercular theory of Cope and Osborn.

According to the theory of Concrescence, the molar teeth originated by the fusion of two or more conical teeth. Embryological evidence in favour of this theory is fragmentally and inconclusive. This is now abandoned in favour of the second theory which is now accepted with certain modifications.

The Cope-Osborn theory of Tritubercular, based on palaeontological evidence postulates that the mammalian molar has been derived from a simple reptilian conical tooth by the development of additional cusps. In the Mesozoic mammals (Pantotheria or Trituberculata) from which modern mammals have evolved, the crown of the molar tooth has three cusps or tubercles arranged more or less in the form of a triangle.

This pattern of tooth has been tritubercular, and it is assumed that the molars of the modem mammals have arisen from this type. The tritubercular tooth itself has arisen from the primitive cone by the development of lateral cusps. Later from these cusps or folds additional cusps or folds develop which finally give rise varied mammalian molars or cheek teeth.

Dental Formula:

One of the important characteristics of mammalian dentition is that the number of teeth in any particular species is so surprisingly constant that it is considered to be of great significance in classification.

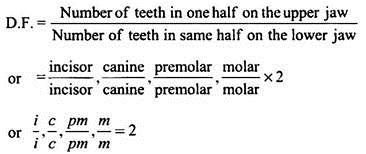

The number of each type of teeth of a mammal or dentition is expressed by a dental formula (D.F.).

The dental formula is expressed as the number of different types of teeth in one half of the upper jaw and is written above a line, while the number of teeth of one half of the lower jaw is written below the line, e.g.:

Since two halves of each jaw are identical, only the teeth of one side are recorded. Those of the upper and lower jaws are separated by a horizontal line. Kinds of teeth are denoted by their initial letters i, c, pm and m representing incisors, canines, premolars and molars, respectively. Number of teeth shown in the formula multiplied by 2 gives the total number of teeth of a species.

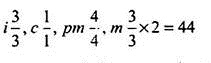

A typical mammalian dentition includes 44 permanent teeth which are shown by the dental formula as follows:

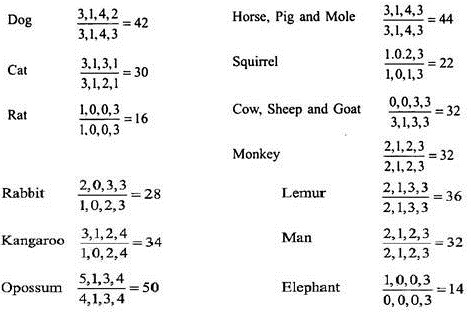

To simplify further, it is customary to omit letters, so that the same formula may be written as 3, 1, 4, 3/3, 1, 4, 3 = 44. When a certain type of teeth is lacking, it is indicated by a zero.

Dental formula of some common mammals is as follows: