The below mentioned article provides notes on zoological nomenclature:- 1. Meaning of Zoological Nomenclature 2. Origin of Binomial System 3. Codes 4. Requisites 5. The International Code 6. Principles.

Meaning of Zoological Nomenclature:

The respective role of classification and nomenclature are often misunderstood. The identification, delimitation and ranking of taxonomic categories are zoological tasks. The role of nomenclature is merely to provide labels for these taxonomic categories in order to facilitate communication amongst biologist. We cannot speak of objects, if they do not have names.

Nomenclature (Latin words: nomen meaning name; clature meaning to call) means a system of name and, thus, is the language of zoology and the rules of nomenclature are its grammar. Since all zoologists deals with animals and use their names for communication, it is, thus, essential that the general principles of zoological nomenclature be familiar to all zoologists, irrespective of whether they are systematist or not.

Origin of Binomial System:

(a) Vernacular names:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

There are in most languages more or less elaborate systems of nomenclature for animals and plants. Hunting people usually have a better knowledge of nature and, consequently, a richer taxonomic nomenclature than agricultural or particularly urban people. The more conspicuous species of mammals, birds, fishes and insects have name in all the languages in the world.

Those applied to major groups of animals are usually short, frequently monosyllabic as bear, finch, fox, sparrow, frog, bee etc. Common names for species are often formed by modifying these group names with respective noun or adjectives thus polar bear, brown bear, snow leopard, black leopard etc. These double names are binomial.

Such common and vernacular names have proved to be inadequate for scientific purposes because they are different in the thousands of languages and dialects of the world. The same name is applied to different organisms in different regions. It is evident that it would be difficult to base a universal nomenclature of scientific names on the vernacular names on one of the living languages.

(b) Scientific Names:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Linnaeus is to be credited with having standardized the system of scientific nomenclature. Even before Linnaeus there was a recognition of the category genus and species, which, in part, goes back to the nomenclature of the primitive people.

Plato definitely recognised two categories, the genus and species, and so did his pupil Aristotle. The naturalists of the pre- Linnaeus era were not consistent to Latin names they gave to plants and animals. These names ranged all the way from uninominal and binomial to polynomial. The reason for this conclusion was that they tried to combine two different functions in the name that is, naming and describing.

The simple system of a unique combination of two names for every species, often called the binomial system, was applied for the first time, introduced by a French naturalist, Linnaeus, in his book Systema Naturae (10th edition, 1758). This work was, therefore, designated in the international rule as the starting point of zoological nomenclature.

Codes of Nomenclature:

The simplicity of the binomial system proved to be tremendously stimulating to taxonomy. It gave any one the authority to apply Latin names to organisms and these names automatically had permanent status, either as valid names or as synonyms. When all the authors had adopted the Linnaean system, a new source of confusion appeared.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Many authors decided to change the existing names if they had not been in corrected form, according to Greek or Latin grammar or if the old names proved to be inapplicable. Geographical names were often changed if they were found to be inaccurate. The result was nomenclature confusion if not anarchy.

The need for a set of definite rules of nomenclature became clear, which had, as a matter of fact already been recognised by Linnaeus (1751), who formulated a personal set of rules.

Eventually the situation became so critical that the British Association for Advancement of Science, appointed a committee to draw up a general set of rules for zoological nomenclature. The resulting code of Strickland (1842) formed the basis of all future codes.

After more than 40 years since then, it had become evident that zoological nomenclature was an international matter and could be handled only by an international set of rules. Hence the first International Zoological Congress held in Paris (1889) adopted a code proposed by Raphael Blanchard. This was actually the beginning of our present international rules.

The present rules are the universal code of nomenclature. At no time since they were formerly adopted has a nationally based system of nomenclature been proposed. The international rules have thus been truly international.

Requisites of Nomenclature:

The important requisites of nomenclature are many, but three are especially significant:

(i) Stability:

As a recognition symbol, the name of objects would lose much of their usefulness if they were changed frequently and arbitrarily. Such changes of well-established names would create confusion and impede information retrieval.

Yet this basic principle of communication has been constantly violated by zoologists. Therefore, even the principle of priority (discussed later) can be set aside by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature in case where stability has been threatened.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Universality:

It would have been very difficult if scientific communications were done for animals, based only on vernacular names. In such a case, specialists would have to learn the names of taxa in innumerable languages in order to facilitate communication with one another. To avoid this, zoologists have adopted, through international agreement, a single language, a single set of names for animals, to be used on a worldwide basis.

(iii) Uniqueness:

A classification is a filing system, an information retrieval system. Like the index number of a file, the name of an animal would immediately give access to all known information about that particular taxon. Every name has to be unique because it is the key to the entire literature relating to that species or higher taxon.

If several names have been given to a particular taxon, then there must be a clear-cut method of determining which of them has validity. However, in zoological nomenclature, priority usually decides in cases of conflict.

These three major objectives of the communication system of taxonomists are singled out for attention in the Preamble of the code: The objective of the code is to promote stability and universality in the scientific names of animals, and to ensure that each name is unique and distinct. All its provisions are subservient to these ends.

The Preamble also stresses another vitally important principle, that none of the provisions of the code restricts the freedom of taxonomic thought or action. It means that no taxonomist shall be forced to accept a particular classification or the delimitation of a taxon or be guided in his or her original choice of the type of a taxon by any but zoological reasons.

The International Code of Nomenclature:

The valid rules of zoological nomenclature are present in an authoritative document entitled the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. The original code was the work of the International Congress of Zoology, which was later taken up by the General Assemblies of IUBS (International Union of Biological Sciences). The International Congress of Zoology appointed a judicial body – the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to interprete the rules and publish opinions on controversial issues.

Priority:

Of all the rules of zoological nomenclature, the most difficult to formulate was the one determining which of the two or more connecting names should be chosen. Owing to the French Revolution (1789) and the Napoleonic wars (1801-1815), there was a period of disturbed communication and taxonomists of one country were often unaware of the new species and genera described by taxonomists in other countries.

Each author used his own judgement as to which name to adopt. The nomenclature chaos prevalent during that period is not appreciated by those contemporary authors, who blamed the rules of nomenclature for all the evils of name changing. The fathers of modern nomenclature believed that the continuous changing of names could be prevented if priority were adopted as a basic principle of nomenclature.

Under this principle it would not be possible to change or replace an earlier name merely because it was incorrectly formed or misleading or for other personal aesthetic or even scientific reasons. It is evident from much of the earliest writings on the subject that the “priority” these authors had in mind was a priority of usage rather than priority of publication.

However, admirable though, the principle of priority of usage is it is subjective and so an attempt was made to restore objectivity by replacing priority of usage with priority of publication. This priority of publication means that when a name is given, it should be a living entity and accompanied by a description.

The Law of Priority:

The Law of priority covers the period from 1st January 1758 to the present. Article 23 of the Code deals specifically with the rules and as amended at Paris in 1948.

Its essential provisions are that the valid names of a genus or species can only be that name under which it was first designated on the conditions:

1. That (Prior to January 1931) this name was published and accompanied by an indication or a definition or a description.

2. That the author has applied the principles of Binomial Nomenclature.

3. That no generic name nor specific trivial name published after December 31st, 1930, shall have any status of availability (hence also of validity) under the rules, unless and until it is published either —

(i) With a statement in words indicating the characters of the genus, species or subspecies concerned.

(ii) In the case of a name proposed as a substitute for a name which is invalid by reason of being a homonym with a reference to the name which is thereby replaced.

(iii) In the case of a generic name or sub-generic name, with a type species designated or indicated in accordance with the one or other of the rules prescribed for determining the type species of a genus or sub-genus, upon the basis of the original publication.

4. That even if a name satisfies all the requirements specified of, that name is not a valid name if it is rejected under the law of homonymy (one name for two or more individuals).

In zoological nomenclature, the principle of priority applies only to the categorical levels of species (and sub-species), genus and family. It, however, does not apply to the higher categories.

Date for Starting Point of Zoological Nomencloture:

The date for starting point of Zoological Nomenclature is January 1,1758. It is the date on which the tenth edition of Linnaeus Systema Naturae was published.

Principles under which Nomenclature Operates:

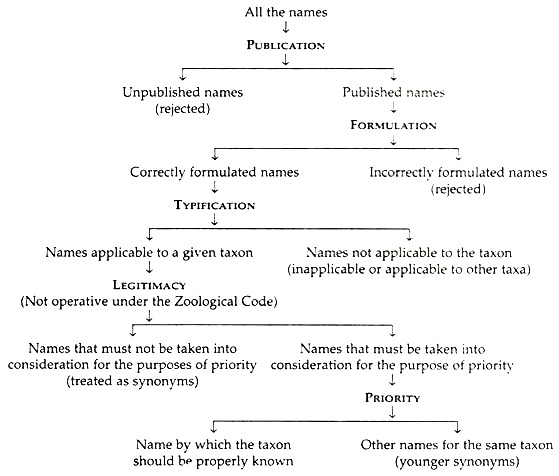

The aim of the Nomenclature Code is to ensure that, with any given circumscription, position and rank a taxon can have one, and only one, name by which it may be properly known. It also tries to reject or avoid the use of names which may create ambiguity or confusion.

To achieve such aims the Code has layed down certain provisions, based on a number of operative principles such as publication, typification, priority etc. The way in which these principles are employed to determine the name by which a taxon should be properly known is given in Table 3.2.

(a) Publication:

Before a properly formulated name can have any status in biological nomenclature, it must fulfill two basic conditions:

(i) It must be published in a medium that is in accordance with the requirements of the appropriate code.

(ii) It must be accompanied by a written matter conforming to the requirement of the code.

If the first condition is fulfilled then the name is said to be published (by zoological code) or effectively published (by Botanical and Bacteriological Codes). The name should be accompanied by some information (description), otherwise it would be difficult to ascertain what kind of organism the name was applied to.

(b) Formulation:

The names should be properly formulated. Those which are not in Latin form, or are otherwise inappropriate to the rank of the taxon concerned, are excluded from use.

(c) Typification:

Often, for a species the descriptions may be insufficient to establish an identity (particularly the short descriptions of earlier workers). Sometimes a description may apply equally well to several later discovered species. As additional species are discovered, the identity of a higher taxa may change, and the higher taxa may have to be split. In such a case which of the components should retain the name?

Thus, a secure standard of reference is needed to tie taxonomic names. These standards are the types and the method of tying names to taxa is called the type method or typification. Under all the three codes (Zoological, Botanical and Bacteriological), the type method is fundamental to the application of names to taxa. A type is purely a nomenclature concept, and has no significance for classification.

In case of zoological code a type is always a zoological object, never a name. The type of a family-group taxon is a genus, the type of a genus-group taxon is a species and the type of a species-group is a specimen. A type, once designated, cannot be changed even by the author of the taxon. It can be changed only through the plenary powers of the Commission, by the designation of a neo-type.

Kinds of Types:

Several kinds of types are recognised by the Code. Some of which are dealt herewith:

(i) Holotype:

Holotype is either the sole element used by the author of a name or the one element designated by him as the type.

(ii) Syntype:

It is either any one of two or more elements used by the author of a name who did not designate a holotype.

(iii) Lectotype:

A lectotype is an element selected subsequently from amongst syn-types to serve as the nomenclature type. In accordance with the Code (Article 74) provided, the designation of a lectotype is based on careful consideration of all the evidences provided by the author of a name in the place of original publication.

(iv) Neo-type:

A neo-type is a specimen selected to serve as the nomenclatural type when through loss or destruction no holotype, lectotype or syntype existed, or when suppressed by the commission. In the selection of neo-type, care and guidance is provided by the Codes.

(v) Para-type:

A specimen cited in the original description, that are neither the holotype nor the lectotype. Para-types have no special standing under the Code and do not qualify as types.

(vi) Monotype:

A holotype based on a single specimen. However, when holotype is correctly designated, it is synonymous with it.

(vii) Topo-type:

The place where the population from which the type specimen was taken is said to be the type locality. Specimens collected at the type locality are called the topo-type and the population that forms at the type locality is called the topo-typical population.

(d) Priority:

A detail on priority has been dealt with earlier. When two or more names apply to the same taxon, then, according to the principles of priority, it is the oldest name that should properly be known, provided it is a valid name according to the Zoological Code.

Limitations of priority:

The operation of the principle of priority has certain limitations, such as:

(i) Starting point dates.

(ii) Limitations associated with rank.

(iii) Exclusion of certain classes of names from consideration for the purpose of priority.

(iv) Procedures for the conservation and rejection of names.

Homonyms:

Homonyms are names spelt in an identical manner for two or more different taxa, but based on different types. If such names come into widespread use, then they create confusion. The earliest of such names are referred to as senior-homonym, while the later names are junior-homonyms. Articles 52 through 60 deals with the validity of homonyms and with replacement names for junior homonyms. They are one of the most difficult areas of zoological nomenclature.

According to the Code, out of the two or more homonyms, all except the oldest (senior homonym), are excluded from use. The junior homonyms can, therefore, never be names by which taxa can properly be known. The Zoological Code excludes from homonymy names those that have never been used for taxa in the animal kingdom.

The Zoological Code explicitly states that two identical species-group names placed in different genera that have homonymous names are not to be considered as homonymy. For example, Noctua variegata of Insecta and Noctua variegata of Aves are not to be considered as homonyms.

Synonyms:

Two or more names given to the same taxon are known as synonyms. The correct establishment of synonymies is one of the most important tasks, as elaboration of a classification and the preparation of keys depend on the correctness and completeness of the synonymies. The oldest of such names is considered to be Senior Synonym while the later ones as Junior Synonyms.

According to the principle of priority, only one name can be accepted by which the taxon may be properly known, and it is, in general, the oldest (senior synonym) one. The later or junior synonyms form what is called the synonymy of the accepted name of the taxon.

For the consultation of taxonomic works it is thus important to distinguish clearly the name accepted as valid from those cited in the synonymy. Modern taxonomic research has to cope with frequent excess of names over taxa.

This has come about in two main ways:

1. Lack of awareness of previously published names.

2. Insufficient appreciation of the amount of variation that can exist within a species. This is the result due to lack of sufficient specimens.

Presently with more material available and greater opportunities for field and experimental studies — there is no dearth of species. Moreover, with modern communications, international taxonomic associations have reduced the likelihood of the same taxon being described more than once under different names. However, keeping abreast of the current literature, synonymy is still a problem in spite of the advent of computerised abstracting and data-handling services.

Taxonomic and nomenclature synonyms:

Two kinds of synonyms are generally present:

1. Nomenclature synonyms:

Nomenclature synonyms are synonyms based upon the same type. Their synonymy are said to be absolute and not a matter of taxonomic opinion. They are also known as obligate, objective or homotypic synonyms.

2. Taxonomic synonyms:

Taxonomic synonyms are synonyms based upon different types. They remain as synonyms only as long as their respective types are considered to belong to the same taxon. They are also known as subjective or heterotypic synonyms. Nomenclatural synonymy are indicated by the mathematical sign of congruence ‘≡’, while the taxonomic synonymy by the sign of equality ‘=’.

Significance of synonymy:

Irrespective of the fact that the names placed by an author in synonymy are not valid, it, however, does not imply that they are of no significance. A considerable amount of information may be recorded in the literature under these invalid names. Therefore, the synonymy of a taxon is a key to information about the taxon, and it is for this reason that taxonomic research is concerned for the establishment of the correct synonym.

Tautonyms:

A tautonym is the name of a species in which the second term exactly repeats the generic name. For example Bison bison, Axis axis, Catla catla, Naja naja etc. Tautonyms are illegitimate under the Botanical Code. However, the Zoological and Bacteriological Codes permit the use of tautonyms.